MPD operates in the private market for SMEs where deals are scanty but the scope of expansion plenty. We scrutinize the best investment opportunities and achieve robust returns through utilizing value creation techniques. In this article, we will walk you through how to create value for both SMEs and investors by using the tool Multiple Boost.

The rule “Buy low, sell high” is particularly felt in the SME deal market where the discount effect on multiples of smaller companies is stronger than in mid/large caps.

SME-focused private equity funds have higher expected returns than peers targeting larger deals with similar strategies.

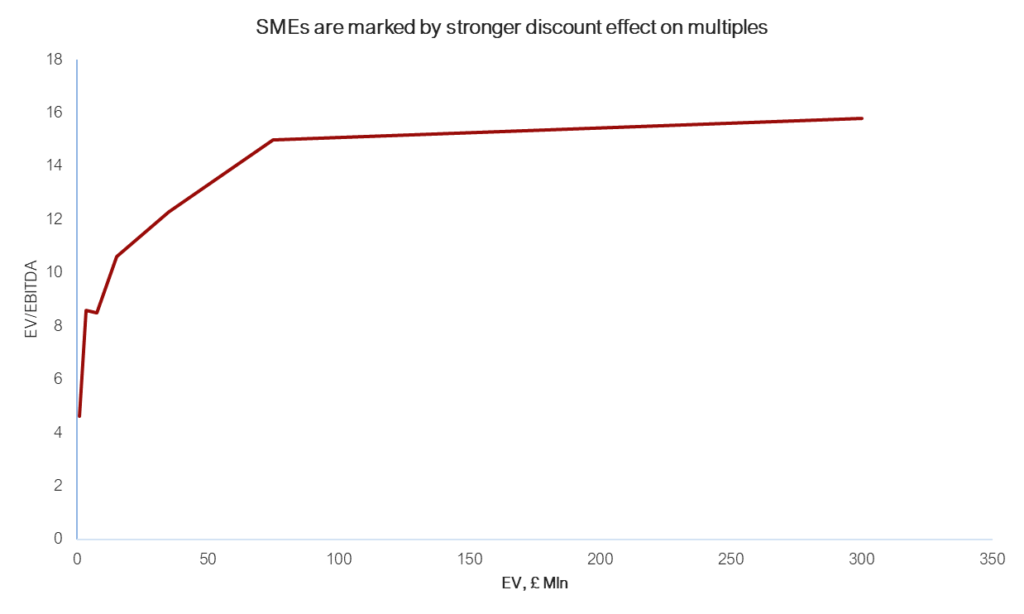

Discounts are applied to SMEs in the deal market since they are riskier and less liquid compared to larger firms in the same business. A study conducted by Menzies1 over a ten-year timespan from 2005 to 2015 on acquisitions of UK companies during a 10-year timespan shows how the size of businesses can affect earnings multiples, which are commonly used for company valuation. Not only do smaller firms have lower earnings multiples compared to larger enterprises, but more interestingly, the discount effect is not linear. As is shown in the figure below, multiples fall faster when enterprise value drops below the threshold of £ 100 million, and in particular for SMEs whose enterprise value fall below £ 5 million. As a result, SME-focused private equity funds have higher expected returns than peers targeting larger deals with similar strategies.

Liquidity is another factor that contributes to discount effect. A more liquid market counts more deals and more market participants from both the sell and the buy sides, adding no effect on the values of companies for sale. In an illiquid market, however, potential buyers need compensations for the difficulties in reselling or, to put it in M&A jargons, divesting the business, thus lowering enterprise multiples used for pricing.

In less active private markets like the one in Italy, illiquidity plays an important role in such analyses and further drives down multiples of smaller enterprises. This makes investors more conservative in valuation, as they must also consider the difficulty in reselling an asset at a reasonable price and other risks related to divestment. Hence, we would expect the deal multiple for an Italian company of the size less than € 2 million to be less than what is suggested by Menzies, which is EV/EBITDA multiple of 4.6x.

Theoretically, such inference is difficult to be backed by statistical significance, as data for deals under € 5 million is highly dispersed and sometimes even incomplete. Although small- and mid-market companies and operators in the deal market should call the investment databases and report numbers, this is not always the truth based on how data speaks.

In practice, we identified a range of EV/EBITDA multiple between 4x and 5x throughout our past track record of over 20 agreed term sheets as the buy and sell-side.

Smaller companies, acquired at a low multiple, can be resold at a higher valuation multiple as a part of a larger entity.

Now that we have covered the “buy low” aspect – acquiring a small company at a discount – how can we ensure that the “sell high” part of the doctrine holds? The answer lies in the multiple boost, a tool for value generation. This differs from the concept of multiple arbitrage, as the latter entails profiting from market mispricing, whereas we focus on value creation through impactful management with a strategic rationale.

MPD Partners grows the value of companies it manages by performing cost cutting, efficiency improvements, and other techniques. For example, Digital Mill, the company that MPD Partners managed and drove to a hefty exit, saw its EBITDA growing from negative € 213 thousand to positive € 629 thousand within one year. Along with the growth in EBITDA, we observed the corresponding increase in the valuation multiple.

The strategic rationale can be better grasped when thinking about a merger. Before accounting for any value addition or integration effects, a combined entity will have higher value than the sum of two standalone firms simply because the new company is larger and considered less risky. Hence, smaller companies, acquired at a low multiple, can be resold at a higher valuation multiple as a part of a larger entity. Getting back to the case of Digital Mill, we also acknowledge that the company value benefited from improved valuation multiple as it was sold as part of a larger transaction, namely, acquisition of DOING by Capgemini.

The relevance of the above can be backed up by the recent trend in the number of add-on transactions in the US. Add-on acquisition is a strategy through which an acquired entity becomes part of the buyer private equity firm’s existing portfolio company. As the add-on target is typically of a smaller size, it is acquired at a low multiple. This consequently allows to decrease the total acquisition multiple of the merged entity and sell at a higher exit multiple. According to the report by Pitchbook, around 70% of all US private equity buyouts is represented by add-ons as of September 2019, compared to only 46% in 2006.

Comparable valuation using multiples is more complicated than it might seem. Each target company has peculiar conditions and must be examined on a case-by-case basis. Adjustments on EBITDA are a good example to demonstrate how analysts must dismiss extraordinary items from the income statement to reflect a true and recurrent situation of the company under examination.

Such extraordinary scenarios are often more frequently observed in SMEs than in big corporations, as the owner of small business, his/her role and compensation in the company could have greater impact on the company’s financials than the extent to which a professional manager’s salary level could alter a big corporation’s performance. A concrete example could be the bonus conferred to the owner-manager of an SME at the end of the year as a tax reduction regime. This bonus and any extraordinary owner salaries need to be added back to calculate recurring EBITDA. Another example would be an alteration relating to the rental price, which should be a number that must reflect the fair market value.

Although the market for SME is less liquid and riskier than it is for companies of a large scale, the discount to valuation of such companies clearly allows to seize value creation opportunities. Suppose we have a company A that has EV of € 10 million and the respective EV/EBITDA multiple of 8x (see the graph above). According the Menzies’ result, if we grow the company to a size of € 30 million, multiple will be boosted to 12x already. If we then merge the company with another company of a larger size, the concerned firm will have an even higher valuation multiple as it’s now been valued as part of a bigger entity. That said, as it has always been the case with valuation multiples, extraordinary items from income statement that could affect denominator of a multiple should not be neglected.

Download full report here: